Episode 3: Adding levels and platforms

Summary

In this episode, we’ll add the ability to load and render a level. After that, we will examine the steps involved in handling physics, and we will make our platforms collidable.

Storing levels

Before we can draw a level to the screen, we need to store the layout of the level. For now, we only need to store the platform tiles, but we will create a data structure that we can add more fields to later (such as the ladder tile data). We’ll call this structure LevelData, and add it to our constants file.

// constants.hpp, inside Constants namespace

// Game area size in tiles

const uint8_t GAME_WIDTH_TILES = GAME_WIDTH / SPRITE_SIZE;

const uint8_t GAME_HEIGHT_TILES = GAME_HEIGHT / SPRITE_SIZE;

// Level data

struct LevelData {

// Platform data

uint8_t platforms[GAME_WIDTH_TILES * GAME_HEIGHT_TILES];

};

// constants.hpp, inside Constants namespace

// Game area size in tiles

const uint8_t GAME_WIDTH_TILES = GAME_WIDTH / SPRITE_SIZE;

const uint8_t GAME_HEIGHT_TILES = GAME_HEIGHT / SPRITE_SIZE;

// Level data

struct LevelData {

// Platform data

uint8_t platforms[GAME_WIDTH_TILES * GAME_HEIGHT_TILES];

};

# constants.py

# Game area size in tiles

GAME_WIDTH_TILES = GAME_WIDTH // SPRITE_SIZE

GAME_HEIGHT_TILES = GAME_HEIGHT // SPRITE_SIZE

# Level data

class LevelData:

def __init__(self, platforms):

# Platform data

self.platforms = platforms

def copy(self):

return LevelData(self.platforms.copy())

For the Python version, we’ve added a method to create a copy of this structure. This is because if we assign an existing list to a new variable, both variables will still refer to the same data, meaning that modifying one list will change the other list too. We’ll need this method later, as we will eventually be editing copies of our level data during gameplay.

Adding our level data

The data for our platforms will be stored as an array, with each index representing an 8x8 square on the screen. If a square consists of empty space, we’ll use 255 (hex value 0xff) to represent this. If the square does contain a tile, we’ll store the spritesheet index of that tile instead.

Although we’ve chosen to use a single-dimensional array, in your own projects, you could use a two-dimensional array instead.

We will store the data for all our levels in a single array, with each item in the array corresponding to a specific level in our game. Each of these items will be an instance of the LevelData data structure that we just defined. We’ll also need to define the number of levels in our game (just one for now, although we’ll add more levels later).

// constants.hpp, inside Constants namespace

// Number of levels

const uint8_t LEVEL_COUNT = 1;

const LevelData LEVELS[LEVEL_COUNT] = {

// Level 1

{

// Platform data

{

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0x03, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x03, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x00, 0x01, 0x02, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0x01, 0x01, 0x01, 0x02, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x00, 0x01, 0x01, 0x01,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0x01, 0x01, 0x01, 0x02, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x00, 0x01, 0x01, 0x01,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x00, 0x01, 0x02, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff

}

}

};

// constants.hpp, inside Constants namespace

// Number of levels

const uint8_t LEVEL_COUNT = 1;

const LevelData LEVELS[LEVEL_COUNT] = {

// Level 1

{

// Platform data

{

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0x03, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x03, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x00, 0x01, 0x02, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0x01, 0x01, 0x01, 0x02, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x00, 0x01, 0x01, 0x01,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0x01, 0x01, 0x01, 0x02, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x00, 0x01, 0x01, 0x01,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x00, 0x01, 0x02, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff

}

}

};

# constants.py

# Number of levels

LEVEL_COUNT = 1

LEVELS = [

# Level 1

LevelData(

# Platform data

[

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0x03, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x03, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x00, 0x01, 0x02, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0x01, 0x01, 0x01, 0x02, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x00, 0x01, 0x01, 0x01,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0x01, 0x01, 0x01, 0x02, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x00, 0x01, 0x01, 0x01,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x00, 0x01, 0x02, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff

]

)

]

If you want to edit the level, you can add/remove platforms by changing the values in the array.

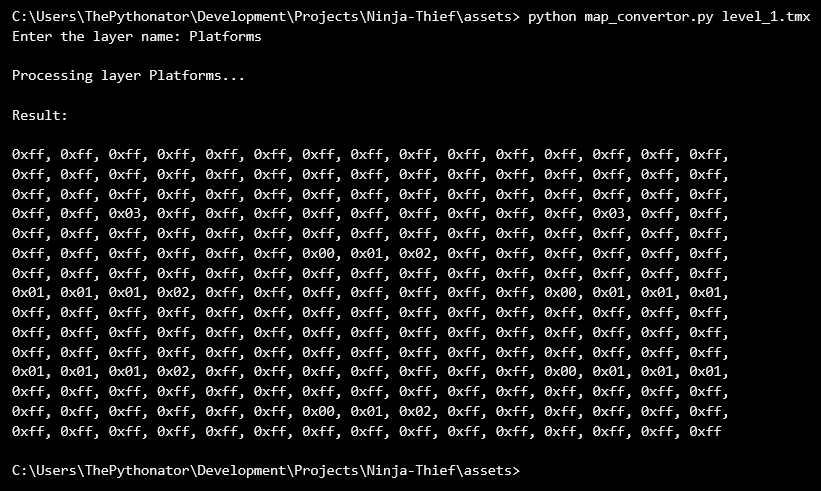

Generating the level data

This section can be skipped if needed, as it only provides additional information on how the level data was generated.

Editing each value individually in the level data arrays is tedious, which is why level editors (such as Tiled) are often used. To make editing our levels easier, this Python script can be used, which takes the csv data stored in a .tmx file and converts it to the format used in this game, ready to be pasted into the array. This allows the levels to be created and edited in Tiled, and the new data added to the constants file with minimal effort.

In order to use the Python script, the pytmx library must be installed:

python3 -m pip install pytmx

If this doesn’t work, try using

pythoninstead ofpython3(also make sure that you have Python 3 installed!)

To run the script, you need to provide it with the path to the .tmx file:

python3 map_convertor.py path/to/map_file.tmx

./map_convertor.py path/to/map_file.tmx

You will then be prompted to enter the name of the layer which will be converted (this isn’t case-sensitive). If you are modifying the pre-existing level files, the layer name should be one of:

Entity SpawnsExtrasPlatformsPipes

If you want to add extra levels, it’s recommended that you copy a pre-existing level file, to use as a template.

The program will then output the data in a comma-separated format which can be pasted directly into your code (the data will not include the surrounding brackets).

The complete program dialogue might look something like this:

The level class

In our game, we will delegate most of the actual game handling to a new class called Level. This class will store and keep track of the player and any enemies, and will render the tiles which comprise the current level. The constructor will take a level number, so that the corresponding level data can be fetched from our constants file.

Currently the PlayerNinja class is instantiated and handled within ninja_thief.cpp (or ninja_thief.py). We will move this code into our new Level class, because the player will be reset each time a new level is started. We’ll also move the code which draws our placeholder score text into the render function of our new class.

Create a new file in include/ called level.hpp (or level.py), with the following code:

// level.hpp

#pragma once

#include <string>

#include "32blit.hpp"

#include "player_ninja.hpp"

#include "constants.hpp"

class Level {

public:

Level();

Level(uint8_t _level_number);

void update(float dt);

void render();

private:

Constants::LevelData level_data = {};

uint8_t level_number = 0;

PlayerNinja player;

};

// level.hpp

#pragma once

#include <string>

#include "picosystem.hpp"

#include "player_ninja.hpp"

#include "constants.hpp"

class Level {

public:

Level();

Level(uint8_t _level_number);

void update(float dt);

void render();

private:

Constants::LevelData level_data = {};

uint8_t level_number = 0;

PlayerNinja player;

};

# level.py

from player_ninja import PlayerNinja

import constants as Constants

class Level:

def __init__(self, level_number):

self.level_number = level_number

self.level_data = Constants.LEVELS[level_number].copy()

# Temporary player object for testing

self.player = PlayerNinja(50, 50)

def update(self, dt):

# Update the player

self.player.update(dt)

def render(self):

# Render the player

self.player.render()

# Set the text colour to white

pen(15, 15, 15)

# Render the placeholder score text

text("Score: 0", 2, 2)

The Python code uses the

copymethod we defined earlier, so that thelevel_dataattribute is a true copy of the data, and not just a reference to an item in theLEVELSlist defined in our constants file.

If you’re using C++, you also need to create a new file in src/ called level.cpp, where we will define our member functions:

// level.cpp

#include "level.hpp"

using namespace blit;

Level::Level() {

}

Level::Level(uint8_t _level_number) {

level_number = _level_number;

level_data = Constants::LEVELS[level_number];

// Temporary player object for testing

player = PlayerNinja(50, 50);

}

void Level::update(float dt) {

// Update player

player.update(dt);

}

void Level::render() {

// Render the player

player.render();

// Set the text colour to white

screen.pen = Pen(255, 255, 255);

// Render the placeholder score text

screen.text("Score: 0", minimal_font, Point(2, 2));

}

// level.cpp

#include "level.hpp"

using namespace picosystem;

Level::Level() {

}

Level::Level(uint8_t _level_number) {

level_number = _level_number;

level_data = Constants::LEVELS[level_number];

// Temporary player object for testing

player = PlayerNinja(50, 50);

}

void Level::update(float dt) {

// Update player

player.update(dt);

}

void Level::render() {

// Render the player

player.render();

// Set the text colour to white

pen(15, 15, 15);

// Render the placeholder score text

text("Score: 0", 2, 2);

}

Tidying up

Since the creation, updating, and rendering of our PlayerNinja instance is handled in the Level class, we can remove the corresponding lines in ninja_thief.cpp (or ninja_thief.py). We will then replace these lines with calls to create, update, and render an instance of our Level class.

We can also remove the placeholder score text, as it has also been moved into our Level class.

Your ninja_thief.cpp (or ninja_thief.py) file should now look like this:

// ninja_thief.cpp

#include "ninja_thief.hpp"

using namespace blit;

// Our global variables are defined here

Surface* background = nullptr;

float last_time = 0.0f;

Level level;

// Setup the game

void init() {

// Set the resolution to 160x120

set_screen_mode(ScreenMode::lores);

// Load the background from assets.cpp

background = Surface::load(asset_background);

// Load the spritesheet from assets.cpp

Surface* spritesheet = Surface::load(asset_spritesheet);

// Set the current spritesheet to the one we just loaded

screen.sprites = spritesheet;

// Load the first level

level = Level(0);

}

// Update the game

void update(uint32_t time) {

// Calculate change in time (in seconds) since last frame

float dt = (time - last_time) / 1000.0f;

last_time = time;

// Limit dt

if (dt > 0.05f) {

dt = 0.05f;

}

// Update level

level.update(dt);

}

// Render the game

void render(uint32_t time) {

// Clear the screen

screen.pen = Pen(0, 0, 0);

screen.clear();

// Draw the entire background image onto the screen at (0, 0)

screen.blit(background, Rect(0, 0, Constants::SCREEN_WIDTH, Constants::SCREEN_HEIGHT), Point(0, 0));

// Render the level

level.render();

}

// ninja_thief.cpp

#include "ninja_thief.hpp"

using namespace picosystem;

// Our global variables are defined here

buffer_t* background = nullptr;

float last_time = 0.0f;

Level level;

// Setup the game

void init() {

// Load the spritesheet

buffer_t* sprites = buffer(Constants::SPRITESHEET_WIDTH, Constants::SPRITESHEET_HEIGHT, asset_spritesheet);

// Set the current spritesheet to the one we just loaded

spritesheet(sprites);

// Load the background

background = buffer(Constants::SCREEN_WIDTH, Constants::SCREEN_HEIGHT, asset_background);

// Load the first level

level = Level(0);

}

// Update the game

void update(uint32_t tick) {

// Calculate change in time (in seconds) since last frame

// The time() function returns the time in milliseconds since the device started

float dt = (time() - last_time) / 1000.0f;

last_time = time();

// Limit dt

if (dt > 0.05f) {

dt = 0.05f;

}

// Update level

level.update(dt);

}

// Render the game

void draw(uint32_t tick) {

// Clear the screen

pen(0, 0, 0);

clear();

// Draw the entire background image onto the screen at (0, 0)

blit(background, 0, 0, Constants::SCREEN_WIDTH, Constants::SCREEN_HEIGHT, 0, 0);

// Render the level

level.render();

}

# ninja_thief.py

from time import ticks_ms, ticks_diff

import constants as Constants

from player_ninja import PlayerNinja

from level import Level

# Perform any initialisation here, at the start of the file

last_time = 0

# Load the first level

level = Level(0)

# Load the spritesheet

sprites = Buffer(Constants.SPRITESHEET_WIDTH, Constants.SPRITESHEET_HEIGHT, "assets/spritesheet.16bpp")

# Set the current spritesheet to the one we just loaded

spritesheet(sprites)

# Load the background

background = Buffer(Constants.SCREEN_WIDTH, Constants.SCREEN_HEIGHT, "assets/background.16bpp")

# Update the game

def update(tick):

global last_time

# Calculate change in time (in seconds) since last frame

# The ticks_diff() function calculates the number of milliseconds between the two times measured

dt = ticks_diff(ticks_ms(), last_time) / 1000

last_time = ticks_ms()

# Limit dt

if dt > 0.05:

dt = 0.05

# Update the level

level.update(dt)

# Render the game

def draw(tick):

# Clear the screen

pen(0, 0, 0)

clear()

# Draw the entire background image onto the screen at (0, 0)

blit(background, 0, 0, Constants.SCREEN_WIDTH, Constants.SCREEN_HEIGHT, 0, 0)

# Render the player

level.render()

# Enter the main game loop

start()

We won’t need to modify this file for quite a while, since most of our work will be in the Level and Ninja classes.

If you are using C++, you need to include the new level.hpp header file in ninja_thief.hpp, as well as remove the temporary include of the player_ninja.hpp file. Your ninja_thief.hpp file should now look like this:

#include "32blit.hpp"

#include "constants.hpp"

#include "level.hpp"

#include "assets.hpp"

#include "picosystem.hpp"

#include "constants.hpp"

#include "level.hpp"

#include "assets.hpp"

Rendering the level

Currently, our platform tile indices are stored in level_data.platforms in the Level class, so we can iterate through this array to get the index of each tile we need to render. We use 255 (hex value 0xff) as the value representing a blank tile, so we’ll need to add this to our constants file:

// constants.hpp, inside Constants namespace

// Add our new constant variable at the end of the pre-existing Sprites namespace

namespace Sprites {

// ...

// A blank tile is represented by 0xff in the level arrays

const uint8_t BLANK_TILE = 0xff;

}

// constants.hpp, inside Constants namespace

// Add our new constant variable at the end of the pre-existing Sprites namespace

namespace Sprites {

// ...

// A blank tile is represented by 0xff in the level arrays

const uint8_t BLANK_TILE = 0xff;

}

# constants.py

# Add our new constant variable at the end of the pre-existing Sprites class

class Sprites:

# ...

# A blank tile is represented by 0xff in the level arrays

BLANK_TILE = 0xff

Our platforms array is one-dimensional, so we need to convert an point (x, y) into an index in this array. We can do this using the formula:

The width variable must be measured in tile units, instead of pixels, so we will use the GAME_WIDTH_TILES constant that we defined earlier.

We have all the constants we need, so we can add our rendering code to the start of the render function in our Level class:

// level.cpp, at the start of the render function

// Render platform tiles

for (uint8_t y = 0; y < Constants::GAME_HEIGHT_TILES; y++) {

for (uint8_t x = 0; x < Constants::GAME_WIDTH_TILES; x++) {

// Calculate tile index

uint8_t tile_id = level_data.platforms[y * Constants::GAME_WIDTH_TILES + x];

// Only render the tile if it isn't a blank tile

if (tile_id != Constants::Sprites::BLANK_TILE) {

// Offset the tiles since the 32blit version has borders on the screen

screen.sprite(tile_id, Point(x * Constants::SPRITE_SIZE + Constants::GAME_OFFSET_X, y * Constants::SPRITE_SIZE + Constants::GAME_OFFSET_Y));

}

}

}

// level.cpp, at the start of the render function

// Render platform tiles

for (uint8_t y = 0; y < Constants::GAME_HEIGHT_TILES; y++) {

for (uint8_t x = 0; x < Constants::GAME_WIDTH_TILES; x++) {

// Calculate tile index

uint8_t tile_id = level_data.platforms[y * Constants::GAME_WIDTH_TILES + x];

// Only render the tile if it isn't a blank tile

if (tile_id != Constants::Sprites::BLANK_TILE) {

sprite(tile_id, x * Constants::SPRITE_SIZE + Constants::GAME_OFFSET_X, y * Constants::SPRITE_SIZE + Constants::GAME_OFFSET_Y);

}

}

}

# level.py, at the start of the render function

# Render platform tiles

for y in range(Constants.GAME_HEIGHT_TILES):

for x in range(Constants.GAME_WIDTH_TILES):

# Calculate tile index

tile_id = self.level_data.platforms[y * Constants.GAME_WIDTH_TILES + x]

# Only render the tile if it isn't a blank tile

if tile_id != Constants.Sprites.BLANK_TILE:

sprite(tile_id, x * Constants.SPRITE_SIZE + Constants.GAME_OFFSET_X, y * Constants.SPRITE_SIZE + Constants.GAME_OFFSET_Y)

When you run the code, the player should behave as before, but the platform tiles are now present:

Adding borders

This section is only for 32blit users - if you are developing for PicoSystem, you can skip this.

The 32blit has a wider screen than the PicoSystem, so we have to add borders in order to keep the main game area the same, to keep the tutorial as similar as possible for both devices.

If you were writing a game which is designed for 32blit only, you could use the full screen width for the game area. In addition, some games (particularly ones with scrolling graphics) work well on both 32blit and PicoSystem without needing borders or different level layouts for each device.

We will create a new method in the Level class where we can put our border-rendering code:

// level.hpp

// ...

class Level {

public:

// ...

private:

void render_border();

// ...

};

This method can be created under the

privateaccess specifier, because we will only ever call it within therendermethod of theLevelclass (it shouldn’t be part of the visible class interface).

In the definition of render_border, we will draw two BORDER_FULL sprites on each side, along with a BORDER_LEFT and BORDER_RIGHT sprite on the corresponding sides. This will fill in the gap between the edge of the screen and the edge of the game area.

// level.cpp

void Level::render_border() {

// Render border (only needed for 32blit, with the wider screen)

// Each row is the same

for (uint8_t y = 0; y < Constants::SCREEN_HEIGHT; y += Constants::SPRITE_SIZE) {

// Left border:

uint8_t x = 0;

// BORDER_FULL sprites

while (x < Constants::GAME_OFFSET_X - Constants::SPRITE_SIZE) {

screen.sprite(Constants::Sprites::BORDER_FULL, Point(x, y));

x += Constants::SPRITE_SIZE;

}

// BORDER_LEFT sprite

screen.sprite(Constants::Sprites::BORDER_LEFT, Point(x, y));

// Right border:

x = Constants::SCREEN_WIDTH;

// BORDER_FULL sprites

while (x > Constants::SCREEN_WIDTH - Constants::GAME_OFFSET_X) {

screen.sprite(Constants::Sprites::BORDER_FULL, Point(x, y));

x -= Constants::SPRITE_SIZE;

}

// BORDER_RIGHT sprite

screen.sprite(Constants::Sprites::BORDER_RIGHT, Point(x, y));

}

}

Finally, we can call this new method from the render method in level.cpp:

// level.cpp

void Level::render() {

// Render border

render_border();

// ...

}

When running the updated code, borders should now be displayed on either side:

Handling physics

Video game physics can be split up into two steps: collision detection, and then collision resolution. Collision detection involves calculating whether two objects are colliding, while collision resolution moves the objects so that they are no longer colliding.

We will add a function to the Ninja class which will handle the collision detection and resolution. It will calculate the tiles which the player could be colliding with, before calling functions to handle platform, ladder, and coin/gem collisions for each of these tiles (we will leave out the ladder and coin/gem functions for now). These functions will all require the information stored in level_data in the Level class, so we will need to modify the signature of several update functions in order to pass this data in as a parameter.

Firstly, we will add the empty handle_collisions and handle_platform functions in the Ninja class:

// ninja.hpp

class Ninja {

public:

// ...

protected:

// ...

private:

void handle_collisions(Constants::LevelData& level_data);

void handle_platform(Constants::LevelData& level_data, uint8_t x, uint8_t y);

};

// ninja.hpp

class Ninja {

public:

// ...

protected:

// ...

private:

void handle_collisions(Constants::LevelData& level_data);

void handle_platform(Constants::LevelData& level_data, uint8_t x, uint8_t y);

};

# ninja.py

class Ninja:

# ...

def handle_collisions(self, level_data):

pass

def handle_platform(self, level_data, x, y):

pass

If you are using C++, you will also need to add the empty function definitions in the source file:

// ninja.cpp

void Ninja::handle_collisions(Constants::LevelData& level_data) {

}

void Ninja::handle_platform(Constants::LevelData& level_data, uint8_t x, uint8_t y) {

}

For the C++ code, we pass

level_databy reference instead of by value, because it is a large data structure and we want to avoid copying it unnecessarily. If you pass a value by reference and do not intend to modify it, it is good practice to pass it as a constant reference (using theconstkeyword), so that accidental modification is prevented. We do not want to passlevel_dataas a constant reference, because we will need to edit it when the player collects coins (we will remove the coins from the level once they are collected).

We now need to update the parameters of any functions which call these new functions, to provide access to level_data:

// In ninja.hpp and player_ninja.hpp

// In ninja.cpp and player_ninja.cpp

// Modify the update function declaration and definition to have the following signature:

void update(float dt, Constants::LevelData& level_data);

// In player_ninja.cpp, in the update function

// Replace:

Ninja::update(dt);

// With:

Ninja::update(dt, level_data);

// In level.cpp, in the update function

// Replace:

player.update(dt);

// With:

player.update(dt, level_data);

// In ninja.hpp and player_ninja.hpp

// In ninja.cpp and player_ninja.cpp

// Modify the update function declaration and definition to have the following signature:

void update(float dt, Constants::LevelData& level_data);

// In player_ninja.cpp, in the update function

// Replace:

Ninja::update(dt);

// With:

Ninja::update(dt, level_data);

// In level.cpp, in the update function

// Replace:

player.update(dt);

// With:

player.update(dt, level_data);

# In ninja.py and player_ninja.py

# Modify the update function definition to have the following signature:

update(dt, level_data)

# In player_ninja.py, in the update function

# Replace:

super().update(dt)

# With:

super().update(dt, level_data)

# In level.py, in the update function

# Replace:

self.player.update(dt)

# With:

self.player.update(dt, self.level_data)

If you are using C++, make sure that you modify the

updatefunction parameters in the source files as well as the header files.

Finally, we can call the (empty) collision handling code from the update function in the Ninja class. The function should now look like this:

// ninja.cpp

void Ninja::update(float dt, Constants::LevelData& level_data) {

// Apply gravity

velocity_y += Constants::Environment::GRAVITY_ACCELERATION * dt;

// Move the ninja

position_x += velocity_x * dt;

position_y += velocity_y * dt;

// Detect and resolve any collisions with platforms, ladders, coins etc

handle_collisions(level_data);

// Update direction the ninja is facing (only if the ninja is moving)

if (velocity_x < 0.0f) {

facing_direction = HorizontalDirection::LEFT;

}

else if (velocity_x > 0.0f) {

facing_direction = HorizontalDirection::RIGHT;

}

}

// ninja.cpp

void Ninja::update(float dt, Constants::LevelData& level_data) {

// Apply gravity

velocity_y += Constants::Environment::GRAVITY_ACCELERATION * dt;

// Move the ninja

position_x += velocity_x * dt;

position_y += velocity_y * dt;

// Detect and resolve any collisions with platforms, ladders, coins etc

handle_collisions(level_data);

// Update direction the ninja is facing (only if the ninja is moving)

if (velocity_x < 0.0f) {

facing_direction = HorizontalDirection::LEFT;

}

else if (velocity_x > 0.0f) {

facing_direction = HorizontalDirection::RIGHT;

}

}

# ninja.py

def update(self, dt, level_data):

# Apply gravity

self.velocity_y += Constants.Environment.GRAVITY_ACCELERATION * dt

# Move the ninja

self.position_y += self.velocity_y * dt

self.position_x += self.velocity_x * dt

# Detect and resolve any collisions with platforms, ladders, coins etc

self.handle_collisions(level_data)

# Update direction the ninja is facing (only if the player is moving)

if self.velocity_x < 0:

self.facing_direction = Ninja.HorizontalDirection.LEFT

elif self.velocity_x > 0:

self.facing_direction = Ninja.HorizontalDirection.RIGHT

Collision detection

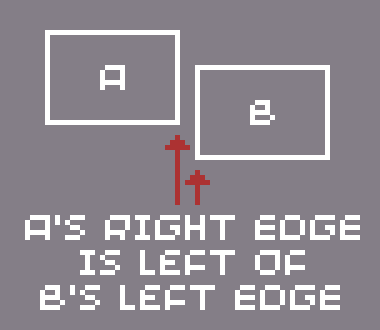

In our game, we can make collision detection simpler by approximating the player and platform tiles as rectangles. This means we only need to know how to check if two rectangles are intersecting.

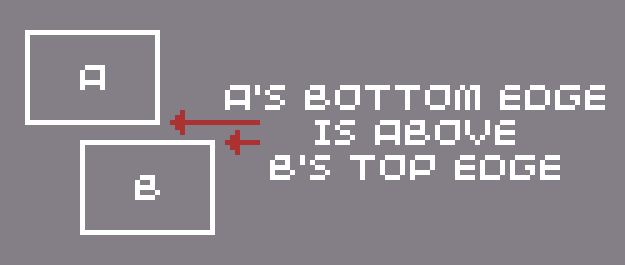

In order to determine if two rectangles (A and B) are intersecting, we can ensure none of the following are true:

- A’s left edge is to the right of B’s right edge

- B’s left edge is to the right of A’s right edge

- A’s top edge is below B’s bottom edge

- B’s top edge is below A’s bottom edge

If either of the first two constraints are true, the rectangles would look something like this:

If either of the last two constraints are true, the rectangles would look something like this:

The coordinates of each object in our game represents the top left corner of the 8x8 sprite used for rendering. For platform tiles, this means we can simply get the right edge position with tile_x + SPRITE_SIZE and the bottom edge position with tile_y + SPRITE_SIZE (the left and top edges are just tile_x and tile_y respectively).

For the ninja sprite, it is slightly more complex, because the sprite does not fill the entire width of the 8x8 square. The height is the same, so the top edge position is given by position_y, and the bottom edge is given by position_y + SPRITE_SIZE. For the width, we must know the visible width of the ninja sprite (which is 4px). With this, we can calculate the number of pixels on each side, between the edge of the sprite square and the edge of the actual ninja image. We will create two new constants called WIDTH and BORDER, with which we can calculate the left and right edges of the ninja’s rectangle. The left edge is given by position_y + BORDER, and the right edge is given by position_y + BORDER + WIDTH.

We will add these constants inside a new namespace (or class in Python) called Ninja:

// constants.hpp, inside Constants namespace

// Generic ninja data such as size

namespace Ninja {

// The visible width of the ninja sprite

const uint8_t WIDTH = 4;

// The gap between the edge of the sprite and the edge of the ninja on each side

const uint8_t BORDER = (SPRITE_SIZE - WIDTH) / 2;

}

// constants.hpp, inside Constants namespace

// Generic ninja data such as size

namespace Ninja {

// The visible width of the ninja sprite

const uint8_t WIDTH = 4;

// The gap between the edge of the sprite and the edge of the ninja on each side

const uint8_t BORDER = (SPRITE_SIZE - WIDTH) / 2;

}

# constants.py

# Generic ninja data such as size

class Ninja:

# The visible width of the ninja sprite

WIDTH = 4

# The gap between the edge of the sprite and the edge of the ninja on each side

BORDER = (SPRITE_SIZE - WIDTH) // 2

We can calculate the location of each edge of a tile and a ninja sprite, so we could write a function which checks for a collision between these two objects. However, we will also need to detect collisions between the player and the coins later on, so we will make the function more generic by taking a parameter specifying the width of the square to check for a collision with.

This means that our collision detection function will perform the following check:

position_x + Constants.Ninja.BORDER + Constants.Ninja.WIDTH > object_x and

position_x + Constants.Ninja.BORDER < object_x + object_size and

position_y + Constants.SPRITE_SIZE > object_y and

position_y < object_y + object_size

The new function will be added to our Ninja class:

// ninja.hpp

// ...

class Ninja {

public:

// ...

bool check_colliding(float object_x, float object_y, uint8_t object_size);

protected:

// ...

};

// ninja.hpp

// ...

class Ninja {

public:

// ...

bool check_colliding(float object_x, float object_y, uint8_t object_size);

protected:

// ...

};

# ninja.py

# ...

class Ninja:

# ...

def check_object_colliding(self, object_x, object_y, object_size):

return (self.position_x + Constants.SPRITE_SIZE - Constants.Ninja.BORDER > object_x and

self.position_x + Constants.Ninja.BORDER < object_x + object_size and

self.position_y + Constants.SPRITE_SIZE > object_y and

self.position_y < object_y + object_size)

In C++, you can use overloading to define multiple functions with the same name, but different parameters. Although our collision detection function will assume that objects are square, you could also write an overloaded version which takes the width and height of the other object.

We will use this feature when we define a collision detection function between two Ninja instances. Python doesn’t directly allow overloading of functions, so we must name our functions slightly differently instead (

check_object_collidingandcheck_ninja_colliding).

If you are using C++, you will also need to add the function definition in the source file:

// ninja.cpp

bool Ninja::check_colliding(float object_x, float object_y, uint8_t object_size) {

return (position_x + Constants::SPRITE_SIZE - Constants::Ninja::BORDER > object_x &&

position_x + Constants::Ninja::BORDER < object_x + object_size &&

position_y + Constants::SPRITE_SIZE > object_y &&

position_y < object_y + object_size);

}

In order to determine which tiles the player is colliding with, we could iterate through every tile in the level_data.platforms array and call our check_colliding function. However, a much more efficient approach is to only check the four tiles surrounding the player’s position.

The position of the top left of these four tiles can be calculated by dividing the player’s position by the tile width and rounding down the result. The other three tile positions can then be calculated by looking at the tiles one block down and to the right of the top left tile. The following visualisation demonstrates which tiles will be tested for a collision:

When the player is near the edge of the game area, we must ensure that we do not try to access tiles which do not exist. Our code will be added to the handle_collisions method in the Ninja class. It checks that the visible player image is within the game area, and if they are at the edge, it only checks the tiles which are within the game area:

// ninja.cpp

void Ninja::handle_collisions(Constants::LevelData& level_data) {

// Get position of ninja in "grid" of tiles

// We're relying on converting to integers to truncate and hence round down

uint8_t x = position_x / Constants::SPRITE_SIZE;

uint8_t y = position_y / Constants::SPRITE_SIZE;

// Check the four tiles which the ninja might be colliding with (the top left tile is marked by the x and y previously calculated)

// We need to check that the player is within the game area

// If they aren't, we don't need to worry about checking for collisions

if (x < Constants::GAME_WIDTH_TILES && y < Constants::GAME_HEIGHT_TILES && position_x >= -Constants::Ninja::BORDER && position_y >= -Constants::SPRITE_SIZE) {

// It's possible the ninja is near the edge of the screen and we could end up checking tiles which don't exist (off the edge of the screen)

// To avoid this issue, we use the ternary operator to vary the maximum x and y offsets

// The minimum offset is handled by the trucation, since it will round up (rather than down) if the value is negative

for (uint8_t y_offset = 0; y_offset < (y == Constants::GAME_HEIGHT_TILES - 1 ? 1 : 2); y_offset++) {

for (uint8_t x_offset = 0; x_offset < (x == Constants::GAME_WIDTH_TILES - 1 ? 1 : 2); x_offset++) {

// Calculate grid position of this tile

uint8_t new_x = x + x_offset;

uint8_t new_y = y + y_offset;

// Handle platforms

handle_platform(level_data, new_x, new_y);

}

}

}

}

// ninja.cpp

void Ninja::handle_collisions(Constants::LevelData& level_data) {

// Get position of ninja in "grid" of tiles

// We're relying on converting to integers to truncate and hence round down

uint8_t x = position_x / Constants::SPRITE_SIZE;

uint8_t y = position_y / Constants::SPRITE_SIZE;

// Check the four tiles which the ninja might be colliding with (the top left tile is marked by the x and y previously calculated)

// We need to check that the player is within the game area

// If they aren't, we don't need to worry about checking for collisions

if (x < Constants::GAME_WIDTH_TILES && y < Constants::GAME_HEIGHT_TILES && position_x >= -Constants::Ninja::BORDER && position_y >= -Constants::SPRITE_SIZE) {

// It's possible the ninja is near the edge of the screen and we could end up checking tiles which don't exist (off the edge of the screen)

// To avoid this issue, we use the ternary operator to vary the maximum x and y offsets

// The minimum offset is handled by the trucation, since it will round up (rather than down) if the value is negative

for (uint8_t y_offset = 0; y_offset < (y == Constants::GAME_HEIGHT_TILES - 1 ? 1 : 2); y_offset++) {

for (uint8_t x_offset = 0; x_offset < (x == Constants::GAME_WIDTH_TILES - 1 ? 1 : 2); x_offset++) {

// Calculate grid position of this tile

uint8_t new_x = x + x_offset;

uint8_t new_y = y + y_offset;

// Handle platforms

handle_platform(level_data, new_x, new_y);

}

}

}

}

# ninja.py

def handle_collisions(self, level_data):

# Get position of ninja in "grid" of tiles

# We're relying on converting to integers to truncate and hence round down

x = int(self.position_x // Constants.SPRITE_SIZE)

y = int(self.position_y // Constants.SPRITE_SIZE)

# We need to check that the player is within the game area

# If they aren't, we don't need to worry about checking for collisions

if x < Constants.GAME_WIDTH_TILES and y < Constants.GAME_HEIGHT_TILES and self.position_x >= -Constants.Ninja.BORDER and self.position_y >= -Constants.SPRITE_SIZE:

# It's possible the ninja is near the edge of the screen and we could end up checking tiles which don't exist (off the edge of the screen)

# To avoid this issue, we use the ternary operator to vary the maximum x and y offsets

# The minimum offset is handled by the trucation, since it will round up (rather than down) if the value is negative

for y_offset in range(1 if y == Constants.GAME_HEIGHT_TILES - 1 else 2):

for x_offset in range(1 if x == Constants.GAME_WIDTH_TILES - 1 else 2):

# Calculate grid position of this tile

new_x = x + x_offset

new_y = y + y_offset

# Handle platforms

self.handle_platform(level_data, new_x, new_y)

In the handle_platform function, we will need to calculate the actual position of the tile (the function receives the grid position), by multiplying the grid position by SPRITE_SIZE. We can then pass this position to our check_colliding (or check_object_colliding) function, in order to determine if the collision resolution code should be called. We will also check that the tile is not an empty tile by fetching the tile’s sprite index from level_data.platforms.

Our handle_platform function in the Ninja class should now look like this:

// ninja.cpp

void Ninja::handle_platform(Constants::LevelData& level_data, uint8_t x, uint8_t y) {

// Get tile's sprite index from level data

uint8_t tile_id = level_data.platforms[y * Constants::GAME_WIDTH_TILES + x];

// Check the tile actually exists (check that it isn't blank)

if (tile_id != Constants::Sprites::BLANK_TILE) {

// Calculate the actual position of the tile from the grid position

float tile_x = x * Constants::SPRITE_SIZE;

float tile_y = y * Constants::SPRITE_SIZE;

// Check if the ninja is colliding with the tile

if (check_colliding(tile_x, tile_y, Constants::SPRITE_SIZE)) {

// Our collision resolution code will be put here

}

}

}

// ninja.cpp

void Ninja::handle_platform(Constants::LevelData& level_data, uint8_t x, uint8_t y) {

// Get tile's sprite index from level data

uint8_t tile_id = level_data.platforms[y * Constants::GAME_WIDTH_TILES + x];

// Check the tile actually exists (check that it isn't blank)

if (tile_id != Constants::Sprites::BLANK_TILE) {

// Calculate the actual position of the tile from the grid position

float tile_x = x * Constants::SPRITE_SIZE;

float tile_y = y * Constants::SPRITE_SIZE;

// Check if the ninja is colliding with the tile

if (check_colliding(tile_x, tile_y, Constants::SPRITE_SIZE)) {

// Our collision resolution code will be put here

}

}

}

# ninja.py

def handle_platform(self, level_data, x, y):

# Get tile's sprite index from level data

tile_id = level_data.platforms[y * Constants.GAME_WIDTH_TILES + x]

# Check the tile actually exists (check that it isn't blank)

if tile_id != Constants.Sprites.BLANK_TILE:

# Calculate the actual position of the tile from the grid position

tile_x = x * Constants.SPRITE_SIZE

tile_y = y * Constants.SPRITE_SIZE

# Check if the ninja is colliding with the tile

if self.check_object_colliding(tile_x, tile_y, Constants.SPRITE_SIZE):

# Our collision resolution code will be put here

pass

In this tutorial, the term “grid position” refers to the position of a tile in the 15x15 grid of possible tile positions. It is measured in tiles, rather than pixels - in order to convert it into the “actual position” of the tile (measured in pixels), we multiple it by the width of a tile in pixels (

SPRITE_SIZE).

We have now written all the collision detection code we will need, and we can move on to the exciting bit - collision resolution! However, if you want to see your code working now, you could always add a print statement where the collision resolution code will go, to check that collisions are being detected at the right times.

Collision resolution

Collision resolution is one of the areas of game development which can cause the most problems for programmers. Game physics is always a trade-off between accuracy and efficiency, and often it is necessary to find a solution which is “good enough” for the specific situation, rather than perfect. For this game, we will use a position-based algorithm because of its simplicity and speed.

Before we get started on resolving collisions with our platforms, we will begin with a much simpler collision detection and resolution problem: stopping the player from walking off the sides of the game area. If the left edge of the player is past the left edge of the game area, we can set position_x so that the left edge of the player lies on the left edge of the game area. We can then do a similar check for the right edge.

We will add this code to the update function in the Ninja class. The function should now look like this:

// ninja.cpp

void Ninja::update(float dt, Constants::LevelData& level_data) {

// Apply gravity

velocity_y += Constants::Environment::GRAVITY_ACCELERATION * dt;

// Move the ninja

position_x += velocity_x * dt;

position_y += velocity_y * dt;

// Don't allow ninja to go off the sides

if (position_x < -Constants::Ninja::BORDER) {

position_x = -Constants::Ninja::BORDER;

}

else if (position_x > Constants::GAME_WIDTH - Constants::Ninja::BORDER - Constants::Ninja::WIDTH) {

position_x = Constants::GAME_WIDTH - Constants::Ninja::BORDER - Constants::Ninja::WIDTH;

}

// Detect and resolve any collisions with platforms, ladders, coins etc

handle_collisions(level_data);

// Update direction the ninja is facing (only if the ninja is moving)

if (velocity_x < 0.0f) {

facing_direction = HorizontalDirection::LEFT;

}

else if (velocity_x > 0.0f) {

facing_direction = HorizontalDirection::RIGHT;

}

}

// ninja.cpp

void Ninja::update(float dt, Constants::LevelData& level_data) {

// Apply gravity

velocity_y += Constants::Environment::GRAVITY_ACCELERATION * dt;

// Move the ninja

position_x += velocity_x * dt;

position_y += velocity_y * dt;

// Don't allow ninja to go off the sides

if (position_x < -Constants::Ninja::BORDER) {

position_x = -Constants::Ninja::BORDER;

}

else if (position_x > Constants::GAME_WIDTH - Constants::Ninja::BORDER - Constants::Ninja::WIDTH) {

position_x = Constants::GAME_WIDTH - Constants::Ninja::BORDER - Constants::Ninja::WIDTH;

}

// Detect and resolve any collisions with platforms, ladders, coins etc

handle_collisions(level_data);

// Update direction the ninja is facing (only if the ninja is moving)

if (velocity_x < 0.0f) {

facing_direction = HorizontalDirection::LEFT;

}

else if (velocity_x > 0.0f) {

facing_direction = HorizontalDirection::RIGHT;

}

}

# ninja.py

def update(self, dt, level_data):

# Apply gravity

self.velocity_y += Constants.Environment.GRAVITY_ACCELERATION * dt

# Move the ninja

self.position_x += self.velocity_x * dt

self.position_y += self.velocity_y * dt

# Don't allow ninja to go off the sides

if self.position_x < -Constants.Ninja.BORDER:

self.position_x = -Constants.Ninja.BORDER

elif self.position_x > Constants.GAME_WIDTH - Constants.Ninja.BORDER - Constants.Ninja.WIDTH:

self.position_x = Constants.GAME_WIDTH - Constants.Ninja.BORDER - Constants.Ninja.WIDTH

# Detect and resolve any collisions with platforms, ladders, coins etc

self.handle_collisions(level_data)

# Update direction the ninja is facing (only if the ninja is moving)

if self.velocity_x < 0:

self.facing_direction = Ninja.HorizontalDirection.LEFT

elif self.velocity_x > 0:

self.facing_direction = Ninja.HorizontalDirection.RIGHT

Remember that the left edge of the player is given by

position_x + BORDER, and the right edge is given byposition_x + BORDER + WIDTH. In the code, these are rearranged slightly so that onlyposition_xis on the left side of the equations and comparisons.

If you run the code now, you will be unable to move out of the game area:

In order to resolve collisions with the platform tiles, we will find the tile edge which intersects the player the least (i.e. has the smallest positive intersection distance), and then move the player away from the edge by this intersection distance. This will result in the player being exactly on the edge of the tile.

This technique doesn’t work well for games with low framerates, as the player can end up moving too far through a platform for the correct collision edge to be found. This results in the player “teleporting” to the opposite side of the block, or being instantly moved left or right to the edge of the block. There are many different alternative collision resolution methods - for example, you can move the player one pixel at a time until they collide with a tile, and then undo the last movement so that they rest on the edge of the tile (this method is less efficient, but works well for games with few collidable objects). More advanced physics engines are often impulse- or force-based, which can produce better, more reliable results (at the expense of increased code complexity and execution time).

Inside the handle_platform function, replace the placeholder comment with the following collision resolution code:

// ninja.cpp, inside handle_platform

// Resolve collision by finding the direction with the least intersection

// The value of the direction variable corresponds to:

// 0 - left side of tile

// 1 - top side of tile

// 2 - right side of tile

// 3 - bottom side of tile

uint8_t direction = 0;

// The starting value of least_intersection is at least the maximum possible intersection

// The width/height of the tile is the maximum intersection possible

float least_intersection = Constants::SPRITE_SIZE;

// Check each side of the tile and find the minimum intersection

// Left side of tile

float intersection = position_x + Constants::Ninja::WIDTH + Constants::Ninja::BORDER - tile_x;

if (intersection < least_intersection) {

direction = 0;

least_intersection = intersection;

}

// Top side of tile

intersection = position_y + Constants::SPRITE_SIZE - tile_y;

if (intersection < least_intersection) {

direction = 1;

least_intersection = intersection;

}

// Right side of tile

intersection = tile_x + Constants::SPRITE_SIZE - position_x - Constants::Ninja::BORDER;

if (intersection < least_intersection) {

direction = 2;

least_intersection = intersection;

}

// Bottom side of tile

intersection = tile_y + Constants::SPRITE_SIZE - position_y;

if (intersection < least_intersection) {

direction = 3;

least_intersection = intersection;

}

// Now resolve collision by moving the ninja in the direction of least intersection, by exactly the amount equal to the least intersection

switch (direction) {

case 0:

// Hit the left side of a platform

position_x -= least_intersection;

velocity_x = 0.0f;

break;

case 1:

// Landed on top of a platform

position_y -= least_intersection;

velocity_y = 0.0f;

break;

case 2:

// Hit the right side of a platform

position_x += least_intersection;

velocity_x = 0.0f;

break;

case 3:

// Hit the underside of a platform

position_y += least_intersection;

velocity_y = 0.0f;

break;

default:

break;

}

// ninja.cpp, inside handle_platform

// Resolve collision by finding the direction with the least intersection

// The value of the direction variable corresponds to:

// 0 - left side of tile

// 1 - top side of tile

// 2 - right side of tile

// 3 - bottom side of tile

uint8_t direction = 0;

// The starting value of least_intersection is at least the maximum possible intersection

// The width/height of the tile is the maximum intersection possible

float least_intersection = Constants::SPRITE_SIZE;

// Check each side of the tile and find the minimum intersection

// Left side of tile

float intersection = position_x + Constants::Ninja::WIDTH + Constants::Ninja::BORDER - tile_x;

if (intersection < least_intersection) {

direction = 0;

least_intersection = intersection;

}

// Top side of tile

intersection = position_y + Constants::SPRITE_SIZE - tile_y;

if (intersection < least_intersection) {

direction = 1;

least_intersection = intersection;

}

// Right side of tile

intersection = tile_x + Constants::SPRITE_SIZE - position_x - Constants::Ninja::BORDER;

if (intersection < least_intersection) {

direction = 2;

least_intersection = intersection;

}

// Bottom side of tile

intersection = tile_y + Constants::SPRITE_SIZE - position_y;

if (intersection < least_intersection) {

direction = 3;

least_intersection = intersection;

}

// Now resolve collision by moving the ninja in the direction of least intersection, by exactly the amount equal to the least intersection

switch (direction) {

case 0:

// Hit the left side of a platform

position_x -= least_intersection;

velocity_x = 0.0f;

break;

case 1:

// Landed on top of a platform

position_y -= least_intersection;

velocity_y = 0.0f;

break;

case 2:

// Hit the right side of a platform

position_x += least_intersection;

velocity_x = 0.0f;

break;

case 3:

// Hit the underside of a platform

position_y += least_intersection;

velocity_y = 0.0f;

break;

default:

break;

}

# ninja.py, inside handle_platform

# Resolve collision by finding the direction with the least intersection

# The value of the direction variable corresponds to:

# 0 - left side of tile

# 1 - top side of tile

# 2 - right side of tile

# 3 - bottom side of tile

direction = 0

# The starting value of least_intersection is at least the maximum possible intersection

# The width/height of the tile is the maximum intersection possible

least_intersection = Constants.SPRITE_SIZE

# Check each side of the tile and find the minimum intersection

# Left side of tile

intersection = self.position_x + Constants.Ninja.WIDTH + Constants.Ninja.BORDER - tile_x

if intersection < least_intersection:

direction = 0

least_intersection = intersection

# Top side of tile

intersection = self.position_y + Constants.SPRITE_SIZE - tile_y

if intersection < least_intersection:

direction = 1

least_intersection = intersection

# Right side of tile

intersection = tile_x + Constants.SPRITE_SIZE - self.position_x - Constants.Ninja.BORDER

if intersection < least_intersection:

direction = 2

least_intersection = intersection

# Bottom side of tile

intersection = tile_y + Constants.SPRITE_SIZE - self.position_y

if intersection < least_intersection:

direction = 3

least_intersection = intersection

# Now resolve collision by moving the ninja in the direction of least intersection, by exactly the amount equal to the least intersection

if direction == 0:

# Hit the left side of a platform

self.position_x -= least_intersection

self.velocity_x = 0

elif direction == 1:

# Landed on top of a platform

self.position_y -= least_intersection

self.velocity_y = 0

elif direction == 2:

# Hit the right side of a platform

self.position_x += least_intersection

self.velocity_x = 0

elif direction == 3:

# Hit the underside of a platform

self.position_y += least_intersection

self.velocity_y = 0

When we move the player to the edge of the tile they collided with, we also set their x or y velocity to 0 (depending on whether they collided with the sides of a tile or the top/bottom). This ensures that they cannot travel through tiles, or build up velocity over time. This is particularly important for the vertical velocity, since the player is always accelerating due to gravity, which would result in extremely high downward velocities if it was never reset.

If you didn’t reset the y velocity when the player collides with the underside of a platform, they would appear to stick to the underside of the platform for a while, before falling back down. Resetting the velocity after a collision means that gravity causes them to start travelling downwards immediately.

Now when you run the code, you will notice that the player doesn’t fall through the platforms anymore, although it is still possible to jump while in midair:

Speeding up MicroPython

You can skip this section if you are not using MicroPython

As we continue developing our game, we will be drawing more sprites to the screen, and performing more calculations each frame. This will result in our game running slower, and the difference is most noticeable for MicroPython, because Python is an interpreted (rather than compiled) language. At lower framerates, the player may fall through platforms and be unable to climb ladders (once we’ve added them), since the lower framerate means they move much further each frame, and collisions get missed.

In order to fix this problem, there are several things we can try. The PicoSystem API allows us to set the blending mode, which determines how pixel colours (and transparencies) are combined when drawing to the screen or another surface. The default setting is ALPHA, which blends the source and destination pixels, taking into account the source pixel’s alpha transparency. This is a slow operation, and increases the rendering time of our game. If we use the MASK option instead, the alpha transparency is ignored (except for completely transparent pixels). This allows us to have sprites with transparency around them (like the ninja sprite), but doesn’t allow us to draw semi-transparent sprites (they will be treated as if they are completely opaque).

We can tell the PicoSystem to use the MASK blend mode by adding the following line at the start of our ninja_thief.py file:

blend(MASK)

Later on, we will draw semi-transparent pipes in the background. This means a lot more sprites will need to be drawn, which would have a significant impact on the framerate with MicroPython. Since it is not part of the gameplay, we will not draw any pipes with MicroPython, in order to maintain the framerate at acceptable levels.

For the more ambitious, it’s possible to add the pipes to the background by rendering them to a copy of the background image at the start of each level. This modified background image can then be rendered each frame, with no additional overhead. This approach requires switching rendering targets using the

targetmethod, which is out of the scope of this tutorial.

Wrapping up

In this episode, we looked at how to store information about our level layout, along with how to render the correct tiles to the screen. We then added the ability to detect collisions with tiles, and used this to determine whether to call the collision resolution code, which stops the player from travelling through any solid tiles.

You can access the source code for the project so far here:

Next episode, we will stop our player from being able to jump in midair, and add ladders which the player can climb up and down. We will also add enemies, starting off with making them patrol the platforms they spawn on, before allowing them to climb ladders as well.